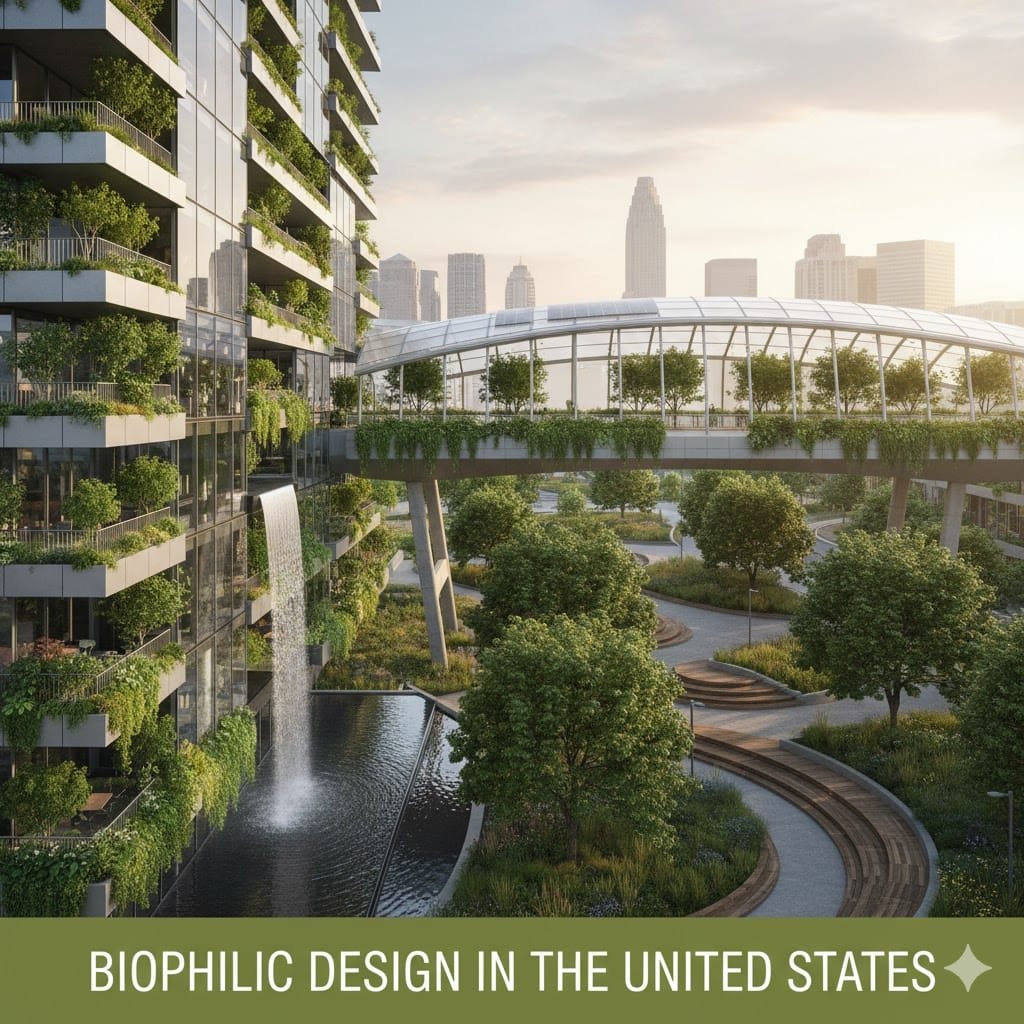

This report provides an exhaustive analysis of the state of biophilic design within the United States, examining its theoretical foundations, quantifiable economic value, and practical integration into the American built environment. Biophilic design has evolved from a nascent academic hypothesis into a codified, evidence-based, and increasingly mainstream pillar of sustainable architecture and design. It is now a critical strategic tool for investors, developers, and corporations seeking to maximize asset value by optimizing human health and performance.

The key findings of this analysis are as follows:

- Maturation from Theory to Practice: Biophilic design, originating with E.O. Wilson’s 1980s “biophilia hypothesis,” has been systematically translated into actionable, measurable design strategies. The work of Stephen R. Kellert established its core principles, and the “14 Patterns” framework from Terrapin Bright Green has become the dominant toolkit used by US practitioners to implement it.

- A Non-Negotiable Return on Investment: The economic case for biophilia is overwhelmingly positive and rests on a critical financial inversion. In the workplace, human capital costs (salaries, benefits, turnover) are 112 times greater than building energy costs. Biophilic interventions have been quantitatively shown to increase productivity by 15%, reduce absenteeism by 10-18%, and save over $2,000 per employee annually, directly targeting this “112x” liability. In healthcare, biophilic design (such as a nature view) has been proven to shorten post-operative hospital stays by 8.5% and reduce pain medication use by 22%, with a potential annual savings of $93 million to the US healthcare system.

- Formal Codification in Green Building Standards: The integration of biophilic design into the dominant US green building standards, LEED and WELL, marks its transition from an optional amenity to a core component of high-value real estate. The WELL v2 standard, in particular, mandates quantifiable biophilic access, while the new LEED v5 framework links biophilia to critical new credits for occupant experience, resilience, and support for neurodiversity.

- A High-Growth, Low-Penetration Market: The US biophilic design market is in a high-growth infancy. The global market is projected to grow at a 10.2% CAGR, yet current biophilic penetration in the $16.64 billion North American office market remains below 5%. This gap represents a significant “arbitrage opportunity” for first-mover investors and developers to capture value by differentiating their assets.

- The Future: Convergence with Resilience and Equity: The future trajectory of biophilic design in the US is one of convergence. It is no longer a standalone concept but is merging with the goals of climate resilience and social equity. Biophilic infrastructure (e.g., green roofs) provides quantifiable resilience benefits (stormwater management, reduced energy load) while also serving as the human-facing justification for these sustainable investments. Furthermore, its integration into policies in cities like Washington D.C., and its new role in supporting neurodiversity, signals a scalable future where biophilia is treated as essential public health and equity infrastructure.

I. A Foundational Imperative: From Hypothesis to Architectural Framework

The entire modern practice of biophilic design is built upon a robust theoretical and academic foundation that traces its origins from a compelling biological hypothesis to a set of actionable frameworks. Understanding this evolution is critical to appreciating its application in the United States, as it explains the “why” behind the movement—the fundamental, non-negotiable human need for nature.

I.A. The Theoretical Bedrock: E.O. Wilson’s Biophilia Hypothesis

The concept of biophilic design originates with the “biophilia hypothesis,” a term introduced and popularized by the seminal American biologist and naturalist Edward O. Wilson in his 1984 book, Biophilia.1 Wilson, a Harvard biologist, defined this hypothesis from a biological and evolutionary perspective, proposing that humans possess an “innate tendency to focus on life and life-like processes”.4

At its core, Wilson’s hypothesis posits that our affinity for nature is not merely a cultural preference but a deep-seated biological need. He argued it is the “innately emotional affiliation of human beings to other living organisms” 4 and, more profoundly, that this “natural affinity for life… is the very essence of our humanity”.3

The hypothesis is rooted in a simple, compelling observation from evolutionary biology. For over 99% of human species’ history, we evolved in “adaptive response to the natural world and not to human created or artificial forces”.5 Our biological systems—our stress responses, our sensory priorities, our cognitive processes—were not shaped in sterile, artificial boxes; they were shaped by the complex, information-rich, and dynamic stimuli of natural ecosystems. Our survival and well-being became biologically encoded to “associate with natural features and processes”.5

The fundamental challenge that biophilic design seeks to address is the severe biological mismatch created by modern urban life. With the average American now spending approximately 90% of their time indoors 5, we have created a “deficiency of contemporary building”.6 This profound disconnect from the natural stimuli we are hardwired to need is a primary contributor to modern stressors, cognitive fatigue, and poor health. Biophilic design, therefore, is not an aesthetic indulgence but a necessary corrective strategy intended to reintroduce these essential, life-affirming connections into the built environments where we spend the vast majority of our lives.1

Wilson’s hypothesis was the critical catalyst for the entire evidence-based design movement. The idea that “nature is good” is intuitive and ancient, but by framing biophilia as an evolutionary adaptation essential for “health, fitness and wellbeing” 5, Wilson elevated the concept from philosophy to biology.7 This biological framing is precisely what empowered subsequent researchers, most notably Roger Ulrich, to form testable hypotheses. If the affiliation with nature is biological, its presence or absence should have a measurable physiological effect on stress, healing, and cognition. This pivotal shift reframed biophilia from a decorative amenity to a vital component of human health infrastructure.

Biophilic Design – VMC GROUP

I.B. Translating Theory to Practice: The Pioneering Work of Stephen R. Kellert

If E.O. Wilson provided the “why,” it was his colleague, the late Yale social ecologist Stephen R. Kellert, who provided the “how”.8 Kellert was the pioneer who translated Wilson’s abstract biological hypothesis into a practical and coherent framework for the built environment.5 He authored and edited numerous foundational texts, including The Biophilia Hypothesis (co-edited with Wilson) and Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life.

Kellert’s framework is two-fold, encompassing principles for both the application of biophilia and the elements of biophilic design. His five principles for effective practice are fundamental conditions for success 6:

- Repeated and Sustained Engagement: Biophilic design is not about a single, isolated experience. It requires repeated and sustained engagement with nature to be effective.6

- Focus on Human Evolutionary Adaptations: The practice must be grounded in Wilson’s hypothesis, focusing on the human adaptations to nature that have advanced health and well-being over evolutionary time.6

- Encourage Emotional Attachment: Biophilic design should foster an emotional attachment to particular settings and places 6, directly combating the “placeless-ness” of generic modern architecture.10

- Promote Positive Interactions: It should promote positive interactions between people and nature that expand our sense of relationship and responsibility for our communities, both human and natural.6

- Demand Integrated Solutions: Biophilic design must encourage mutually reinforcing, interconnected, and integrated architectural solutions.6

This fifth principle is Kellert’s most crucial and challenging contribution. He explicitly warned against the “separate and piecemeal application” of natural elements.6 His vision was not for nature to be a “decorative background” 6 or a token green wall, but for the creation of a holistic, integrated ecological whole where diverse applications complement one another.6 This holistic vision, however, directly clashes with the fragmented, siloed nature of the US architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) industry 11, where disciplines often work in isolation. This “consciousness gap” 5—the gap between a technical “piecemeal” approach and a holistic, values-based one—remains a primary systemic barrier to implementation, which will be explored in Section VI.B.

To guide designers, Kellert also defined six core elements (also referred to as principles) of biophilic design, which remain widely cited 8:

- Environmental Features: The direct, physical presence of natural elements in a space, such as plants, water, animals, sunlight, and fresh air.8

- Natural Shapes and Forms: The symbolic representation of nature through non-living elements. This includes botanical, tree-like, and animal motifs, as well as biomorphic forms (e.g., curved furniture).8

- Natural Patterns and Processes: The inclusion of properties and processes found in nature, such as sensory variability, information richness, and the “patina of time” (natural aging and change).8

- Light and Space: A focus on the qualities of light, particularly natural daylighting, and the creation of spatial experiences that mimic nature.8

- Place-Based Relationships: Rooting a building in its specific context by connecting it to the local geography, history, and ecology.8

- Evolved Human-Nature Relationships: Creating spatial configurations that tap into our evolutionary psychological preferences, such as a desire for Prospect and Refuge (a safe, enclosed space with a long view), Order and Complexity, and Curiosity and Enticement.10

Kellert’s profound impact on translating theory to practice is now honored by the US-based International Living Future Institute (ILFI), which administers the prestigious Stephen R. Kellert Biophilic Design Award to recognize projects that exemplify his principles.14

I.C. The Practitioner’s Toolkit: Terrapin Bright Green’s 14 Patterns

While Kellert provided the foundational philosophy, the New York-based consulting firm Terrapin Bright Green provided the dominant practical toolkit. Their 2014 white paper, “14 Patterns of Biophilic Design,” is arguably the most influential document for practicing architects and designers in the United States.15 It was created specifically to “close the gap between current research and implementation” 15 and “enhance health and well-being… through design”.18

This framework “productized” biophilia, breaking Kellert’s broader concepts into a menu of 14 specific, specifiable, and actionable patterns. This menu-like structure is what allowed the abstract idea to be integrated into the rigid, point-based systems of building certification standards like LEED and WELL.19 The 14 Patterns became the “familiar framework or language” 19 that US professionals could use to justify, implement, and certify their designs.

Read: Biophilic Design in Illinois and Indiana: Principles, Applications, and Regional Insights

The 14 Patterns are organized into three categories 15:

- Nature in the Space (Direct Experience)

This category involves the direct, physical, and ephemeral presence of nature in a space.

- 1. Visual Connection with Nature: A view to elements of nature, living systems, and natural processes, such as a green wall, an aquarium, or a window view of a park.15

- 2. Non-Visual Connection with Nature: Auditory, haptic, olfactory, or gustatory stimuli that create a deliberate reference to nature, such as the sound of birdsong or a water feature, or the smell of flowers.15

- 3. Non-Rhythmic Sensory Stimuli: Stochastic, unpredictable, and ephemeral connections with nature, such as the “swaying of grasses,” “buzz of passing insects,” or the play of light and shadow.15

- 4. Thermal & Airflow Variability: Subtle changes in air temperature, relative humidity, and airflow that mimic natural environments and feel like the outdoors.15

- 5. Presence of Water: The enhanced experience of water, whether through seeing, hearing, or touching it. This includes fountains, water walls, and ponds.15

- 6. Dynamic & Diffuse Light: Leveraging varying intensities of light and shadow that change over time, mimicking natural cycles and conditions.15

- 7. Connection with Natural Systems: Awareness of natural processes as they unfold, such as seasonal changes visible through a window.15

- Natural Analogues (Indirect Experience)

This category involves the non-living, indirect evocation of nature through objects, materials, patterns, and forms.

- 8. Biomorphic Forms & Patterns: The symbolic, non-living representation of nature in design, such as botanical motifs, columnar supports, or organic, non-rectilinear shapes.12

- 9. Material Connection with Nature: The use of natural materials (or materials that mimic them) with minimal processing, such as wood, stone, or natural fibers, that reflect the local ecology.15

- 10. Complexity & Order: The inclusion of rich, organized, and hierarchical information and detail, similar to the fractal patterns found in nature.15

- Nature of the Space (Spatial Experience)

This category involves configuring space to evoke core human psychological responses to natural environments.

- 11. Prospect: An unimpeded, long-distance view over an environment, creating a sense of safety, control, and awareness.

- 12. Refuge: A place of withdrawal, enclosure, and protection from environmental conditions or threats, offering a sense of security.

- 13. Mystery: The promise of more information, enticing an individual to move deeper into a space to explore and learn.

- 14. Risk/Peril: A safe experience of an apparent risk or threat, such as a view from a high, protected balcony, which creates a positive thrill.

.15

These two frameworks, Kellert’s 6 Elements and Terrapin’s 14 Patterns, are the foundational language of biophilic design in the US. The following table provides a comparative analysis, mapping Kellert’s broader concepts to Terrapin’s specific patterns.

Table 1: Framework Comparison: Kellert’s 6 Elements vs. Terrapin’s 14 Patterns

| Kellert’s 6 Elements | Core Concept | Corresponding Terrapin 14 Patterns |

| Environmental Features | Direct, physical experience of nature. | P1: Visual Connection with Nature

P2: Non-Visual Connection with Nature P4: Thermal & Airflow Variability P5: Presence of Water P6: Dynamic & Diffuse Light |

| Natural Shapes and Forms | Symbolic, non-living representation. | P8: Biomorphic Forms & Patterns |

| Natural Patterns and Processes | Dynamic processes and sensory richness. | P3: Non-Rhythmic Sensory Stimuli

P7: Connection with Natural Systems P10: Complexity & Order |

| Light and Space | Spatial qualities of light and shadow. | P6: Dynamic & Diffuse Light |

| Place-Based Relationships | Connection to local context and ecology. | P7: Connection with Natural Systems

P9: Material Connection with Nature |

| Evolved Human-Nature Relationships | Innate psychological responses to space. | P11: Prospect

P12: Refuge P13: Mystery P14: Risk/Peril |

II. The Quantifiable Return: Evidence-Based Impacts in US Sectors

The widespread adoption of biophilic design in the United States is not being driven by aesthetics alone, but by a large and growing body of data that provides a compelling, evidence-based business case. The entire economic argument for biophilia rests on a crucial inversion of traditional green building metrics.

Historically, the ROI for sustainable design focused on building operational costs—namely, energy and water savings. This focus, while important, misses the single largest cost center for any US organization: its people. In a typical workplace, human capital costs (salaries, benefits, turnover) are 112 times greater than energy costs.21

Simultaneously, the US faces a significant human capital crisis. A staggering 70% of American employees report being “not engaged” at work, a phenomenon that costs the US economy an estimated $450 to $550 billion annually in lost productivity.22 Poor worker well-being, often linked to sterile office environments, can cost businesses 25-35% of their total payroll.22

Biophilic design’s primary value proposition is that it directly addresses this “112x” liability, not the “1x” energy cost. It is a direct investment in human performance, health, and well-being. This reframes biophilic design as a core business strategy for managing human capital, not merely an environmental one.

II.A. The Productivity Mandate: Biophilia in the American Workplace

In the corporate sector, biophilic design is a powerful tool for boosting productivity, reducing absenteeism, and winning the “war for talent.”

Productivity and Cognitive Function:

The introduction of natural elements into the workplace has been shown to have a direct, positive impact on employee output. A series of studies from Exeter University concluded that employees were 15% more productive when “lean” offices were filled with just a few houseplants.23 The same study from Human Spaces revealed that workplaces with strong biophilic elements increased employee creativity by 15%.24 The consensus from multiple studies is that biophilic design can “reduce stress, improve cognitive function and creativity” 16, all of which are critical for a knowledge-based economy.

Absenteeism and Stress Reduction:

The financial drain from absenteeism is a major liability. A landmark study from the University of Oregon found that 10% of all employee absences could be attributed to “architectural elements that did not connect with nature”.21 The single primary predictor of absenteeism was the quality of an employee’s view.21

- Employees with views of trees and landscape took an average of 57 hours of sick leave per year.

- Employees with no view (or a view of only a brick wall) took 68 hours of sick leave per year.26

This 11-hour difference per employee translates into a significant, bankable saving. Terrapin Bright Green calculates that providing access to nature views can save over $2,000 per employee per year in reduced absenteeism and associated costs.26 This is corroborated by other research, which found that access to good daylight alone was linked to 18% fewer sick days.24

Talent Attraction and Retention:

The modern workplace is a key tool in attracting and retaining top talent. With the cost of replacing a salaried employee estimated at 6 to 9 months of their salary, high turnover is a massive financial liability.22 A thoughtfully designed, biophilic workspace “sends a powerful message” about an organization’s values and its commitment to employee well-being, which in turn helps “attract and retain the best talent”.23

The Physiological Mechanism:

These benefits are not merely perceived; they are physiological. Biophilic design works by alleviating the chronic stress response endemic to modern offices. In a sterile, high-pressure environment, the body’s sympathetic nervous system (the “fight or flight” response) is over-activated. This is a state of high alert. Exposure to natural elements and patterns activates the parasympathetic nervous system (the “rest and digest” response), which calms the body.23 Biophilic design helps the body achieve homeostasis—a natural balance between these two systems—which results in measurably lower blood pressure, reduced muscle tension, and lower levels of stress hormones.21

II.B. Case Study Spotlight: The 1995 Herman Miller “Productivity Doubled” Precedent

One of the earliest and most dramatic tests of biophilic design in a US corporate setting occurred in 1995 at a Herman Miller manufacturing facility.27 The design, a departure from the “windowless box” typical of industrial architecture, incorporated significant natural lighting and “greater access to outdoor views” for its workers.27

The results were described as “revolutionary”.27 The facility’s energy bill dropped significantly due to the natural lighting. But the human impact was even greater: worker productivity doubled, and employee retention soared.27

The significance of the Herman Miller study cannot be overstated. It is arguably the most important US corporate case study because it proves biophilia’s effectiveness in a manufacturing setting, expanding its ROI case beyond white-collar “knowledge work.” Most case studies focus on corporate HQs like Apple or Google, where the benefits are tied to cognitive or creative tasks. The Herman Miller study demonstrates that the physiological benefits of biophilia—improved focus, reduced fatigue, enhanced well-being—apply equally to repetitive, task-oriented manufacturing and logistics work. This is critical for the US economy, as it extends the business case for biophilic design to the entire industrial and logistics real estate sector, a sector that has historically been built on a “cost-per-square-foot” model that completely ignores human factors.

II.C. The Healing Environment: Biophilia in US Healthcare

The most robust, long-standing, and compelling data for biophilic design comes from the US healthcare sector. Here, the benefits are not measured in productivity, but in human recovery.

The Seminal Study: Dr. Roger Ulrich (1984)

The entire field of evidence-based healthcare design was arguably launched by a 1984 study led by Dr. Roger Ulrich.28 The study was simple, but its findings were profound. It analyzed the recovery records of patients undergoing gallbladder surgery in a suburban Pennsylvania hospital.28 The patients were in identical rooms, with one variable changed:

- Half the patients had a room with a view of a brick wall.

- The other half had a room with a view of nature (a small grove of trees and water).28

The results were statistically undeniable 26:

- Faster Recovery Time: The nature-view group had 8.5% shorter postoperative hospital stays (an average of 7.96 days vs. 8.71 days for the brick-wall group).

- Reduced Pain Medication: The nature-view group required 22% less moderate and strong pain medication.

- Fewer Complications: The nature-view group had fewer negative observations from nursing staff, such as “upset and needed encouragement”.29

Modern Corroboration and Financial Impact:

In the decades since Ulrich’s study, his findings have been repeatedly validated. Subsequent research has found that optimizing natural light can reduce patient hospital stays by up to 41%.28 The financial implications for the high-cost US healthcare system are massive. It is estimated that simply providing patients with views to nature could save $93 million in annual US healthcare costs.26

This impact extends beyond the patients. Biophilic environments are crucial for mitigating the high-stress nature of clinical work, and have been shown to reduce staff stress and burnout.30 In 95% of cases, exposure to nature in a hospital setting also lowered stress levels for families and improved their ability to cope.29 For a hospital, which operates on thin margins, reducing staff burnout (and subsequent turnover) and improving patient and family satisfaction are critical operational and financial goals.

II.D. Application Spotlight: The Rise of the “Healing Garden”

The “healing garden” is the direct architectural application of this decades-long body of research. It is a space designed not for simple aesthetics, but as an active therapeutic environment.31 These gardens provide a “temporary sanctuary” 29 for patients, families, and staff, offering a place for mental respite and stress reduction.

The efficacy of these spaces is rooted in established psychological frameworks. Attention Restoration Theory (ART) posits that nature restores the ability to concentrate after “directed attention fatigue”.32 Stress Recovery Theory (SRT) proposes that exposure to natural environments alleviates the physical and psychological damage caused by stressors.32

These theories have been put into practice in healthcare facilities across the US, including:

- The Comfort Garden at San Francisco General Hospital.33

- The Roof Garden at Alta Bates Medical Center in Berkeley, California.33

- The Central Garden at Kaiser Permanente in Walnut Creek, California.33

- The Whitman-Walker Healing Garden in Washington, D.C..34

The following table synthesizes the most potent, data-backed evidence for biophilic design, serving as an “at-a-glance” business case for stakeholders in the US.

Table 2: Quantified Benefits of Biophilic Design in US Workplaces and Healthcare

| Sector | Metric | Quantified Impact | Source(s) |

| Workplace | Productivity | +15% in offices with biophilic elements | 23 |

| Workplace | Creativity | +15% in offices with biophilic elements | 24 |

| Workplace | Absenteeism (Poor View) | +11 hours/employee/year (68 hrs vs 57 hrs) | 26 |

| Workplace | Absenteeism (Poor Daylight) | +18% reported sick days | 24 |

| Workplace | Annual Savings (View) | $2,000 per employee | 26 |

| Healthcare | Patient Recovery (Nature View) | 8.5% shorter post-operative stay | 26 |

| Healthcare | Pain Medication (Nature View) | -22% use of strong medication | 28 |

| Healthcare | Patient Recovery (Daylight) | Up to 41% shorter hospital stay | 28 |

| Healthcare | Annual US Savings (Views) | $93 Million | 26 |

| Healthcare | Staff Well-being | Reduced stress and burnout | 30 |

| Healthcare | Family Well-being | 95% report lower stress | 29 |

III. Codifying Nature: Integration with US Green Building Standards

The most significant catalyst for the market-wide adoption of biophilic design in the United States has been its formal integration into the two dominant green building certification systems: LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) and the WELL Building Standard.

This codification marks the maturation of biophilia from a “soft” design concept to a “hard,” measurable, and certifiable asset. It provides the technical language and financial incentive (points) for developers and architects to justify the investment to capital partners. A developer may struggle to secure financing for “creating a sense of awe”.10 However, they can and do secure financing for buildings designed to achieve LEED Platinum or WELL Gold certification. By embedding biophilia into these standards, the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) and the International WELL Building Institute (IWBI) have effectively translated the health and productivity benefits (detailed in Section II) into a marketable asset. Achieving these credits has a direct, positive impact on lease rates, asset valuation, and corporate brand positioning, thereby de-risking the upfront investment.

III.A. Biophilia in LEED: The v5 Evolution to Human-Centered Design

The evolution from LEED v4 to the new LEED v5 (in development) represents a major paradigmatic shift for the USGBC. While LEED v4 “primarily emphasized reducing environmental impact,” the new LEED v5 “promotes enhancing human experience”.35 This human-centered approach has elevated biophilic design from a minor innovation credit to a “core strategy, not just an optional extra”.35

This new focus is reflected in several key credits within the Indoor Environmental Quality (EQ) category:

- EQ Credit: Occupant Experience: This new credit (worth up to 7 points) directly rewards integrated biophilic strategies. It includes points for “Natural Environment Integration”—such as living walls and water features that function as air purifiers and acoustic buffers—and “Optimized Natural Light and Views,” which encourages positioning greenery to frame views and reduce glare.35

- EQ Credit: Accessibility and Inclusion: This is a groundbreaking new credit for the US market that creates a powerful social and business case for biophilia. The credit specifically acknowledges that well-designed biophilic environments provide “sensory regulation benefits for people with autism, ADHD, and other neurological differences”.35 This explicitly links biophilia to the “S” (Social) in ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) reporting and corporate Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) goals.

- EQ Credit: Resilient Spaces (EQc4): This new credit aligns biophilic design with climate resilience, rewarding features such as operable windows for natural ventilation 37, which is a key biophilic pattern (P4: Thermal & Airflow Variability).

The new “Accessibility and Inclusion” credit in LEED v5 is a game-changer for the US corporate landscape. It creates a new legal, ethical, and talent-based driver for biophilic design. For a US corporation, creating an “inclusive” workplace 38 is a pressing talent and legal imperative, particularly in light of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). By linking biophilic features (e.g., “quiet retreat zones with natural elements,” “calming textures, gentle scents”) 35 to the documented sensory needs of a neurodiverse workforce 35, LEED v5 provides a verifiable framework for companies to meet their HR, DEI, and legal obligations. This elevates biophilic design from a simple wellness perk to a strategic C-suite tool for human capital management.

III.B. Biophilia in the WELL Building Standard v2: Mandating Nature in the “Mind” Concept

While LEED is broadening to include human health, the WELL Building Standard is an “evidence-based roadmap” 39 focused entirely on human health and well-being. Unsurprisingly, biophilia is a central and mandatory component, featured prominently within the “Mind” concept.19

WELL v2 utilizes both qualitative (pre-condition) and quantitative (optimization) features to ensure biophilia is thoughtfully integrated:

- M02: Access to Nature (Qualitative): This feature is a Precondition for some projects, requiring them to develop a “biophilia plan”.40 This plan must describe how the project incorporates nature directly (e.g., plants, light, water) and indirectly (e.g., natural materials, biomorphic patterns).40 This requirement, similar to Kellert’s fifth principle, pushes teams to integrate biophilia as a holistic strategy, not a piecemeal afterthought.

- M07: Restorative Spaces (Optimization): This feature awards points for providing dedicated indoor (M07.1) and outdoor (M07.2) spaces designed for “complementation, relaxation, and restoration”.40 A key design criterion for these spaces is the “incorporation of nature”.40

- M09: Enhanced Access to Nature (Optimization): This is the key quantitative feature that drives design decisions. To earn points, a project must achieve at least two of the following four stringent, measurable requirements 40:

- Outdoor Nature Access: At least 25% of the project’s exterior site area consists of accessible landscaped grounds or rooftop gardens.

- Indoor Nature Access: At least 75% of all workstations and seating areas have a direct line of sight to indoor plants or a water feature.

- Outdoor Nature Views: At least 75% of all workstations and seating areas have a direct line of sight to outdoor landscapes or nature.

- Nearby Nature Access: The project is located within a 300-meter (approx. 1,000-foot) walking distance of a green or blue space (park or water body) that is at least 0.5 hectares (1.2 acres).

These quantitative metrics, particularly the “75% rule,” are a game-changer for the US real estate industry. They transform “nature access” from a subjective wish into a hard, measurable, and auditable performance indicator. This metric can be modeled in a floor plan and verified post-occupancy. It directly punishes the design of deep, windowless office floor plates and rewards open-plan layouts 41, thoughtful interior landscaping 37, and investment in properties with good views or park proximity.

This hard metric provides a clear, data-driven benchmark for asset valuation, allowing an analyst or investor to differentiate a truly biophilic building from one that is not. It also incentivizes “credit stacking,” where a single design choice can earn points across multiple categories. For example, specifying natural wood or stone (non-VOC materials) 42 can simultaneously contribute to Materials credits (X06: VOC Restrictions, X07: Materials Transparency) and Mind credits (M02: Access to Nature).

The following table provides a technical guide for practitioners to navigate the biophilic design pathways in both LEED v5 and WELL v2.

Table 3: Biophilic Design Pathways in LEED v5 and WELL v2

| Standard | Relevant Credit / Feature | Requirement / Goal | Actionable Biophilic Strategy (Citing Sources) |

| LEED v5 | EQ: Accessibility & Inclusion | Support neurodiversity and sensory regulation. | “Design quiet retreat zones with natural elements” 35; Use “calming textures, gentle scents”.35 |

| LEED v5 | EQ: Occupant Experience | Natural environment integration and optimized views. | “Create authentic ecosystem experiences indoors through living walls” 35; “Position greenery to frame views”.35 |

| LEED v5 | EQ: Resilient Spaces | Ensure adaptability to disruptions and health emergencies. | Install “operable windows” for natural ventilation 37 (P4: Thermal & Airflow Variability). |

| WELL v2 | M02: Access to Nature | (Precondition) Develop a “biophilia plan.” | Integrate direct (plants, light) and indirect (natural materials, patterns) connections.40 |

| WELL v2 | M09: Enhanced Access to Nature | Achieve 2 of 4 quantitative metrics. | Ensure “75% of all workstations” have “direct line of sight” to indoor plants, water features, or outdoor landscapes.40 |

| WELL v2 | M07: Restorative Spaces | Provide designated indoor/outdoor spaces for relaxation. | “Nature incorporation” 40; “Sound masking” (e.g., water feature 43); “Sense of enclosure and refuge”.44 |

| WELL v2 | X06: VOC Restrictions / X07: Materials Transparency | Use healthy, non-toxic materials. | Specify “natural materials such as stone, wood, bamboo and cork” which contain no VOCs 42 (P9: Material Connection). |

IV. The Economics of Biophilia: Market Dynamics and The Business Case

Beyond its theoretical foundations and evidence-based health benefits, biophilic design is a significant and accelerating economic force in the United States. Its adoption is increasingly framed as a core investment strategy, driven by compelling market growth, a clear return on investment (ROI) that dwarfs traditional sustainability metrics, and a favorable lifecycle cost analysis.

IV.A. Market Size, Growth, and Penetration

The market for biophilic design is demonstrating robust growth, signaling a clear upward trend in adoption.

- Global Market: The global biophilic design market is projected to reach US$3.14 billion by 2028. This represents a strong Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 10.2% over the analysis period from 2023 to 2028.45

- US Market Context: The United States is the engine of this market. The US interior design market accounted for a dominant 83.21% revenue share of the total North American market in 2023.46

- Key Driver: This massive US market is being “driven by… the growing popularity of sustainable and energy-efficient designs” and, crucially, a “significant focus on… wellness-oriented spaces, with a focus on biophilic design“.46

- Sector Leadership: The retail and hospitality sectors are projected to be leaders in adopting biophilic trends in 2025.47 In an era of e-commerce, biophilia is a key strategy for “experience per square foot,” which has become a primary brand differentiator to draw customers into physical stores.48

- Market Penetration: Despite this high growth, the market is far from saturated. In the $16.64 billion North American office furniture market, biophilic penetration remains less than 5%.47

The analysis of this data reveals a classic high-growth, low-penetration market. For an investment analyst, a 10.2% CAGR 45 is a strong signal. When coupled with less than 5% market penetration 47, it signals that the market is not saturated; it is in its infancy. The 95% of the market still utilizing “traditional office solutions” 47 represents the total addressable market (TAM) for biophilic disruption. This data confirms that the “unprecedented arbitrage opportunity” 47 for first-mover developers, investors, and suppliers is real and that the growth runway is exceptionally long.

IV.B. The Definitive ROI: Why Human Costs (112x) Outweigh Energy Costs

The central economic thesis for biophilic design, as established in Section II, is its focus on the “112x” human cost rather than the “1x” energy cost.21 This argument is predicated on viewing poor workplace environments not as a static condition, but as a massive, quantifiable liability on a company’s balance sheet.

The Liability (The Problem):

- Engagement & Productivity: Actively disengaged employees, who constitute the majority of the US workforce (70%), cost the US economy $450 to $550 billion per year.22

- Health Costs: Poor worker health, often exacerbated by poor indoor environments, costs US companies 25% to 35% of their total payroll.22

- Turnover Costs: Employee retention is the top workforce challenge for HR leaders. The cost to replace a single salaried employee is, on average, 6 to 9 months of that employee’s salary.22

The Asset (The Solution):

Biophilic design is a direct capital investment to mitigate these enormous, ongoing liabilities. Its ROI is not measured in years, but often in months. A study of a public authority building in Sacramento provides a clear, micro-level example of this ROI in action 21:

- The Intervention: Desks were rotated to give employees views of trees, providing “restorative mental pauses”.21

- The Cost: Approximately $1,000 per occupant.

- The Return: Call-handling productivity increased by more than 6%.

- The ROI: The productivity gain resulted in savings of approximately $3,000 per occupant, a 3:1 return on the initial investment.21

This is the business case: biophilic design is an asset that pays for itself by reducing absenteeism 26, improving focus 21, and boosting well-being 23, all of which directly target the largest and most volatile cost-center a company has: its people.

IV.C. Deconstructing Initial Costs vs. Long-Term Lifecycle Value

The most common barrier to adoption cited by US developers is the “perception of high risks and costs” 49 and high upfront investment.22 However, a proper Lifecycle Cost Analysis (LCA) 52 reveals that biophilic design is, in fact, the more economic choice, as it adds tangible value across the building’s entire life.

A traditional, non-biophilic building’s “cheaper” sticker price is an illusion. It is cheap only because it externalizes its true costs, which are later paid by the occupant in higher utility bills, by the tenant in higher employee turnover, and by the municipality in higher public infrastructure costs. Biophilic design internalizes and solves these costs, generating a long-term return.

- Energy Savings: Biophilic strategies are inherently sustainable. Green roofs and living walls act as natural insulation, reducing heating and cooling energy costs by 20-50%.53 Strategic daylighting and window placement can cut artificial lighting costs by up to 60%.53 The 1995 Herman Miller facility, for example, saw a “revolutionary impact” on its energy bill.27

- Stormwater Management Savings: In urban areas, managing stormwater is a massive municipal expense. Biophilic infrastructure—such as green roofs, rain gardens, and permeable pavements—can cost 10-30% less than conventional “grey” infrastructure (pipes, tanks, and treatment systems).53

- Building Lifespan and Maintenance Savings: Biophilic elements protect the building. A living wall or green roof shields the building’s facade and waterproof membrane from UV radiation and extreme heat, extending the building’s lifespan and reducing long-term maintenance and replacement costs.53

This data demonstrates that traditional construction is the more expensive choice over the long term. Biophilic design is the more economic choice, but its value is captured over the entire lifecycle of the asset, not just at the moment of construction. This LCA data is the critical tool for developers to justify the investment to their capital partners.

The following table provides a clear cost-benefit analysis for key biophilic interventions, arming stakeholders to overcome the “upfront cost” barrier.

Table 4: Cost-Benefit Analysis: Initial Investment vs. Long-Term Lifecycle ROI

| Biophilic Intervention | Relative Upfront Cost | Operational ROI (Building) | Human Capital ROI (Occupant) |

| Green Roof / Living Wall | High | Reduces energy costs 20-50%.

Reduces stormwater mgt. costs 10-30%. Extends roof membrane lifespan. |

Reduces stress; Provides P1: Visual Connection; Mitigates urban heat island effect. |

| Interior Daylighting / Windows | Medium-High | Reduces artificial lighting costs up to 60%. | 18% fewer sick days 24; 10% of absenteeism linked to poor views; Saves $2,000/employee/year. |

| Natural Materials (Wood, Stone) | Low-Medium | Durable; Low-maintenance; Can be locally sourced. | Reduces stress 54; Achieves P9: Material Connection; Contributes to WELL Materials credits.42 |

| Interior Plants / Water Feature | Low | Improves indoor air quality 55; Provides acoustic masking.43 | +15% productivity; Reduces stress; Achieves P1: Visual Connection & P5: Presence of Water. |

| Biophilic Infrastructure (Bioswales) | Medium | Costs 10-30% less than grey infrastructure. | Manages stormwater; Improves air quality; Creates visual amenity. |

V. Application in Practice: US Case Studies and Industry Leadership

The principles and economic benefits of biophilic design are being actively proven at scale by a cohort of pioneering organizations, architectural firms, and landmark projects across the United States. These examples have moved biophilia from a theoretical concept to a built reality, creating a set of influential, real-world case studies.

V.A. Key Organizations and US Firms Defining the Movement

A dedicated ecosystem of non-profits, consultancies, and design firms, largely based in the US, has been instrumental in advancing the biophilic movement.

Organizational Drivers:

- International Living Future Institute (ILFI): This US-based non-profit is a key global advocate. Its Biophilic Design Initiative 56 was created to provide the practical “how-to” resources for implementation, bridging the gap from theory to reality.56 The ILFI also administers the prestigious Stephen R. Kellert Biophilic Design Award, which celebrates the best built-projects that exemplify Kellert’s principles.14

- Terrapin Bright Green: A New York-based environmental consulting and design firm. They are the authors of the two foundational documents that underpin the modern practice: the “14 Patterns of Biophilic Design” 15 and “The Economics of Biophilia”.26

Leading US-Based Architectural Firms:

- COOKFOX Architects (New York, NY): This firm is an outspoken leader in the field, stating that biophilia is their “one-word mantra” 57 and building a reputation for “nature inspired architecture”.58

- Key Projects: One Bryant Park (the first commercial skyscraper to achieve LEED Platinum) 57; their own former studio at 641 Avenue of the Americas, which became an iconic case study for its integrated, accessible green roof 60; and innovative facade R&D, creating terracotta systems to serve as habitats for birds and bees.62

- Mithun (Seattle, WA): A major US firm built on a “Design for Health” ethos.63 Mithun Partner Bert Gregory was a contributing author to Stephen Kellert’s seminal book Biophilic Design.63

- Key Projects: The 200 Occidental building in Seattle, noted for its visual and material connections to nature 63; the Coeur d’Alene Tribe Resort Expansion, which integrated the unique ecology and culture of the tribe 64; and significant R&D into applying biophilic mass timber design to K-12 schools.65

- Snøhetta (New York, NY): A globally renowned, interdisciplinary firm with a major US studio in New York.66

- Key Projects: The firm is currently leading the design of the highly anticipated Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library in Medora, North Dakota, a project deeply integrated into the landscape.67

- Gensler (Global, major US presence): As one of the world’s largest firms, Gensler has integrated biophilia into major corporate projects, including the Adobe headquarters in San Jose, California.68

- HOK (Global, major US presence): A leader in healthcare design, HOK designed the award-winning Barnes Jewish Hospital—Center for Advanced Medicine in St. Louis 69 and the award-winning New York-Presbyterian Integrative Health and Well-being Center.44

V.B. Landmark Case Studies in Corporate Architecture

Several high-profile US corporate campuses have become global symbols of biophilic design, serving as large-scale experiments in workplace productivity and brand identity.

- Apple Park (Cupertino, CA): Perhaps the most “widely recognised example” of large-scale biophilic architecture.70 The design is an act of biophilia-as-brand.

- Features: Rather than imposing on the land, the building “embraces the shape of the land”.70 It is surrounded by a man-made forest of approximately 9,000 trees.70 The iconic circular building features a vast “hollowed-out centre full of wildlife,” providing thousands of employees with a direct, park-like connection to nature.70

- Google (Chicago, IL & New York, NY): Google’s corporate offices are frequently cited as examples of biophilic integration.

- Features: The Chicago office renovation is noted for its “commitment to employee well-being” by incorporating “natural elements, sustainable materials, and a focus on natural light”.72

- Amazon “The Spheres” (Seattle, WA): This project represents one of the most direct applications of biophilia. The Spheres are a trio of glass domes that function as an immersive, jungle-like greenhouse, containing over 40,000 plants. It serves as an employee lounge and collaborative workspace, providing a total immersion in nature in the middle of a dense urban campus.

- Adobe (San Jose, CA): The Gensler-designed headquarters utilizes a “wide scope of biophilic principles,” ranging from subtle interventions (natural color choices) to overt features (large-scale nature murals).68

V.C. Landmark Case Studies in Healthcare Design

Following the data from Ulrich and others, US healthcare systems are investing heavily in biophilic design as a core component of patient care and staff retention.

- New Stanford Hospital (Palo Alto, CA): This project, designed by Rafael Viñoly Architects and Perkins Eastman, is a model for “human-centered design” and biophilia in a high-acuity setting.73

- Features: The hospital includes a massive four acres of gardens.74 The third floor is known as the “garden floor,” featuring five interconnected rooftop gardens with walking paths and views of the nearby hills.74 Most importantly, in a move toward equitable biophilia, floor-to-ceiling windows are standard in every patient room, ensuring all patients receive the documented healing benefits of natural light and views.75

- Bronson Methodist Hospital (Kalamazoo, MI): An award-winning replacement campus 77 designed by Shepley Bulfinch.

- Features: The hospital was lauded by jurors for its “innovative integration of healthcare services, art, and the natural environment”.69 A key feature includes an indoor garden, bringing nature inside for patients and staff year-round.78

- VA Puget Sound Mental Health & Research Building (Seattle, WA): A LEED-certified facility designed by Stantec to serve a sensitive patient population.79

- Features: The design focuses on creating calm, therapeutic environments. It includes a grass-covered rooftop, rainwater harvesting for irrigation, interior landscaped courtyards 79, and a “peaceful indoor rock garden” to create quiet, restorative spaces.80

A clear trend emerges from these leading US healthcare case studies: an evolution from passive biophilia to integrated and equitable biophilia. The 1984 Ulrich study was binary: a patient happened to get a good view or a bad view. This created an equity problem. The New Stanford Hospital solves this by making floor-to-ceiling windows a standard of care for every patient.75 The VA Puget Sound and Bronson Methodist facilities solve it by bringing nature inside to atriums, indoor gardens, and rock gardens.78 This makes the biophilic experience accessible to all patients, families, and staff, regardless of their room assignment, moving biophilia from a perk to a clinical tool.

V.D. Landmark Case Studies in Public and Urban Spaces

The most significant recent trend in the US is the scaling of biophilic design from individual buildings to the urban and municipal level, recognized as a form of green infrastructure.

- Paley Park (New York, NY): Completed in 1967, this “pocket park” is a classic, early example of “biophilic urban acupuncture”.60

- Features: In a tiny 4,200-square-foot footprint, it provides a powerful biophilic experience. Its defining element is a 20-foot-tall waterfall that provides a Non-Visual Connection with Nature (P2) by generating enough white noise (up to 90 decibels) to drown out the sounds of Manhattan traffic.60 This, combined with a dense canopy of honey locust trees and moveable seating, creates an urban oasis that is a powerful example of Refuge (P12), Dynamic & Diffuse Light (P6), and Thermal & Airflow Variability (P4).60

- One River North (Denver, CO): This 2024 residential tower exemplifies biophilia as structure.

- Features: The building’s glass facade is “cracked” by a 10-story vertical canyon of terraced balconies and outdoor spaces, which includes extensive landscaping and a waterfall.81 It integrates nature vertically into the building’s very form.

- The Biophilic Cities Network (National): A global network (launched in 2013) of cities committed to planning and designing with nature.82 The network includes several US partner cities, such as Washington D.C., Arlington, VA, and Charlottesville, VA.84

- Washington D.C. (Policy Case Study): D.C., a partner city since 2015 84, is a prime example of using policy as a biophilic design tool.

- Policy Mandates: The Sustainable DC Plan mandates a 40% city-wide tree canopy and ensures all residents have access to a park within a 10-minute walk.84

- Policy Tools: D.C. has adopted a Green Area Ratio (GAR) requirement for new development in several zones, which forces developers to integrate landscape and site design standards (e.g., green roofs).84 It also created a Stormwater Retention Credit Trading Program, which provides a financial incentive for private green infrastructure, effectively creating a market for biophilia.84

This scaling of biophilia from individual buildings to municipal policy is the most significant trend in the United States. Paley Park was a private, optional intervention.60 The Washington D.C. policies are public, mandatory, and city-wide.84 This represents a profound shift in thinking. The D.C. government is defining biophilic elements (green space, tree canopy) as critical public infrastructure—as essential as roads or sewers—because they provide measurable, non-optional public benefits, including stormwater management 84, climate regulation 87, and equitable public health.84

VI. Implementation in the United States: Barriers, Challenges, and Strategic Solutions

Despite the proven benefits and growing number of successful case studies, the widespread adoption of biophilic design in the United States faces significant, practical, and systemic barriers. These range from high-level cultural resistance to on-the-ground technical challenges. However, for each barrier, a set of strategic solutions is emerging.

VI.A. Navigating Practical Hurdles: Cost, Maintenance, and Knowledge

These are the most common, project-level objections faced by design and development teams.

- Budget Constraints: The “perception of high risks and costs” 49 is the primary barrier. Stakeholders perceive biophilic elements like living walls or water features as expensive, complex, and a “value-add” that can be cut to save money.50

- Solution: The most effective mitigation is a robust, data-driven business case. This involves presenting the ROI and Lifecycle Cost Analysis (LCA) data from Section IV.21 This reframes “cost” as “investment.” Teams can also prioritize lower-cost, high-impact strategies, such as focusing on Natural Analogues (P8, P9, P10) like natural materials, biomorphic forms, and natural color palettes, which are less expensive than complex living systems.50 Using low-maintenance native plants or high-quality preserved moss walls can also provide the visual benefit without the high operational cost.44

- Maintenance Requirements: This is a “crucial but often overlooked” 37 lifecycle risk. Living walls, interior gardens, and water features are not “set it and forget it” installations. They are resource-intensive systems that require specialized, long-term care for irrigation, pruning, and pest control. Failure to plan for this leads to visible failure (dead plants), which negates the psychological benefit.50

- Solution: A comprehensive maintenance plan and budget must be established from day one.88 This involves engaging professional maintenance companies 50 and specifying automated systems for irrigation, monitoring, and lighting to ensure the long-term health and success of the biophilic elements.88

- Lack of Knowledge & Expertise: Many US design and construction teams lack the “specialized knowledge” 88 for the technical integration of biophilic systems. This includes understanding the HVAC implications of added humidity from plants and water, the structural load requirements for green roofs, and the complex irrigation and drainage needed for living walls.50

- Solution: The solution is to “collaborate with experts” 88 and “engage biophilic design early”.37 Bringing a specialized biophilic design consultant, landscape architect, and the correct engineers into the project during the initial concept stage is critical, rather than attempting to “add” biophilia later in the design process.

- Space and Integration: In dense urban environments, implementation can be challenging due to “limited space”.50 It can also be difficult to “integrate with existing design” aesthetics, color palettes, and structural limitations, especially in renovation projects.50

- Solution: For limited space, the solution is vertical. “Living walls, green partitions, or hanging planters” can introduce greenery without occupying valuable floor space.50 For integration, the focus should be on indirect patterns (P8-P14). A “Refuge” space (P12), a “Material Connection with Nature” (P9) through wood flooring, or “Biomorphic Forms” (P8) in furniture can be integrated seamlessly into an existing aesthetic.

VI.B. Overcoming Systemic Barriers: Codes, Culture, and Consciousness

These are the high-level, industry-wide challenges that hinder biophilia from becoming the default standard.

- Fragmented Industry: The US AEC (Architecture, Engineering, Construction) industry traditionally operates in “silos”.11 The architect designs, then hands off to the engineer, who hands off to the contractor. This “traditional linear workflow” 11 is fundamentally incompatible with biophilic design, which, as Kellert argued, must be “ecologically inter-related” and “integrated” to be successful.6

- Solution: A shift in process is required, moving toward Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) models. This model brings all stakeholders—the architect, biophilic consultant, HVAC engineer, and maintenance provider—to the table at the concept stage 37 to develop a holistic, integrated solution from the beginning.

- Outdated Regulations: Biophilic design often runs into regulatory barriers. “Outdated and unsuitable legislation and planning processes” 49 are a major hurdle. Many US building codes, which are “predicated on a separation from” nature 11, lack standards for novel installations like interior water features or large-scale living walls, creating uncertainty for developers and regulators.

- Solution: This requires proactive engagement with municipal code officials. Design teams can use policy precedents from pioneering US cities like Washington D.C., presenting its Green Area Ratio (GAR) 84 as a model for how to safely and effectively codify biophilic integration.

- The “Consciousness Gap”: The ultimate barrier is cultural. Kellert argued that the successful application of biophilia depends less on new techniques and more on “adopting a new consciousness toward nature”.5 It is a value system 6, and a shift from viewing a building as an inanimate box to viewing it as a living habitat.

- Solution: This “consciousness gap” is closed by evidence. The hard, quantifiable data on productivity (Section II.A), patient recovery (Section II.C), and lifecycle economics (Section IV.C) is the tool to change the consciousness of the data-driven US stakeholders who make the final decisions: the investors, developers, and corporate executives.

The following table provides an actionable framework for identifying and mitigating these common barriers.

Table 5: Implementation Barriers and Mitigation Strategies in the US

| Barrier Type | Specific Challenge (Citing Sources) | Strategic Solution / Mitigation |

| Financial | “Budget Constraints” / “Perception of high… costs” 49 | Present the 112x Human Cost ROI 21 and Lifecycle Cost Analysis 53 to investors. Prioritize low-cost, high-impact Natural Analogues (P8-P10). |

| Operational | “Maintenance Requirements” / “Long-term care” 50 | “Develop a maintenance plan” 88 and include it in the operational budget from Day 1. Use automated irrigation systems 88 and professional service contracts.50 |

| Technical | “Lack of Knowledge and Expertise” / “Technical Integration” 50 | “Engage Biophilic Design Early”.37 “Collaborate with experts” 88 (e.g., biophilic consultants, HVAC engineers) from the concept stage. |

| Systemic | “Fragmentation, poor communication” in AEC industry 11 | Utilize Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) models. Mandate cross-disciplinary collaboration from the project’s inception.37 |

| Regulatory | “Outdated and unsuitable legislation” / “Building codes” 11 | Engage code officials early. Advocate for policy reform using precedents like Washington D.C.’s Green Area Ratio (GAR).84 |

| Cultural | The “Consciousness Gap” / A “piecemeal” (vs. holistic) approach 5 | Use the hard, quantitative data from Sections II and IV to align the value system of biophilia with the financial goals of stakeholders. |

VII. The Future Trajectory (2025 and Beyond): Biophilia as Standard Practice

The analysis of the theoretical, evidential, and economic drivers indicates a clear and accelerating future for biophilic design in the United States. It is moving from a niche “trend” to a foundational component of all high-performing real estate. As we look to 2025 and beyond, the practice is evolving, converging with other major industry movements, and solidifying its role as a necessary standard.

VII.A. Emerging Trends: From “Greenery” to Immersive Sensory Environments

The “2025 biophilic home design trend” is described as more than a style; it’s a “lifestyle shift” 89 and the “future of interior design”.41 The market is rapidly maturing beyond the simple “add a few plants” approach to a more sophisticated, integrated, and sensory-based practice.

- Trend 1: The Wellness-First Mindset: The primary driver is wellness.89 The focus is shifting from pure aesthetics (“looking good”) to occupant experience (“feeling better”).89 In both residential and commercial design, clients are demanding spaces that help them “relax, recharge, and feel grounded”.41 This wellness-first mindset is driving adoption across all US sectors, including workplace, hospitality, education, and healthcare.41

- Trend 2: Multi-Sensory and Material Focus: The future of biophilia is less literal and more sensory and analogous. This is a practical response to the maintenance and cost barriers of living systems. Designers are increasingly achieving biophilic goals through:

- Tactile Surfaces: An emphasis on Terrapin’s Pattern P9 (Material Connection). This includes “lightly finished wood, tactile textiles, and raw, textured surfaces” like “honed stone or rough-sawn timber”.41 These elements are high-impact, low-maintenance, and engage the haptic (touch) senses.

- Natural Color Palettes: A move toward “warm, earthy shades like clay or terracotta” or “calming… deep blues or greens” that evoke “soil, sea, and forest”.90

- Trend 3: Data-Driven Design: As biophilia becomes a larger capital investment, stakeholders will demand proof of performance. The future will involve a “more data-driven approach” 91, using indoor environmental quality (IEQ) sensors, wearable technology, and post-occupancy evaluations to validate which biophilic interventions provide the greatest measurable health, well-being, and productivity benefits for a specific space.

VII.B. The Convergence: Biophilia, Resilience, and Sustainable Design

Biophilic design is no longer a separate discipline. It is converging with the two other dominant movements in US architecture—sustainability and resilience—to form a single, unified value proposition.

- Sustainability: Biophilia is inherently part of “sustainable home design” 89 and “promotes sustainability”.1

- Resilience: “Resilient Design” is a top architectural trend for 2025 92 and, as noted, is now a formal credit in LEED v5.37

Biophilia serves as the human-facing component of these two movements. It provides the crucial human health and well-being justification for what are often large investments in green infrastructure.

A green roof is the perfect example of this three-pillared convergence 53:

- It is Sustainable: It manages stormwater, reduces carbon emissions, and promotes biodiversity.93

- It is Resilient: It insulates the building (reducing energy load), mitigates the urban heat island effect, and extends the roof’s lifespan.53

- It is Biophilic: It provides occupants with a Visual Connection to Nature (P1) and a Restorative Space (M07), which measurably reduces stress and improves well-being.26

In the past, a US developer might have rejected a green roof on the basis of its high upfront cost. Today, the combined business case—spanning energy savings (sustainability), risk mitigation (resilience), and human health and productivity (biophilia)—makes the investment not only viable but strategically intelligent. Biophilia is the new, powerful addition to that value proposition.

VII.C. Strategic Outlook: The Inevitable Shift to a Wellness-First Mindset

The evolutionary path of biophilic design in the United States is clear.

- It began as an Academic Hypothesis (Wilson, 1984).2

- It was Quantified by empirical science (Ulrich, 1984).28

- It was Codified by industry standards (Terrapin, 2014; LEED; WELL).15

- It is being Proven at Scale by market-leading US corporations and healthcare systems (Apple, Stanford).70

- It is now being Mandated by public policy as critical infrastructure (Washington D.C.).84

The future of American architecture and interior design is not about “adding nature” as a final decorative layer. It is about a fundamental, data-backed recognition that “prioritizing wellness is no longer a niche approach. It’s a necessary and responsible part of creating spaces that serve the people who use them”.41

For the US market—for its investors, developers, architects, and corporate tenants—biophilic design is the essential framework for designing, building, and operating this new, human-centric, and highly valuable class of real estate assets.

Works cited

- Understanding the Biophilia Hypothesis – TerraMai, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.terramai.com/blog/understanding-biophilia-hypothesis/

- Biophilia Hypothesis: The basis of Biophilic Design – ArchPsych., accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.archpsych.co.uk/post/biophilia-hypothesis-and-biophilic-design

- Biophilia – Harvard University Press, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.hup.harvard.edu/books/9780674074422

- A Meta-Analysis of Emotional Evidence for the Biophilia Hypothesis and Implications for Biophilic Design – PubMed Central, accessed November 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9186521/

- What Is and Is Not Biophilic Design – Metropolis Magazine, accessed November 11, 2025, https://metropolismag.com/viewpoints/what-is-and-is-not-biophilic-design/

- THE PRACTICE OF BIOPHILIC DESIGN – Biophilic Net-Positive …, accessed November 11, 2025, https://biophilicdesign.umn.edu/sites/biophilic-net-positive.umn.edu/files/2021-09/2015_Kellert%20_The_Practice_of_Biophilic_Design.pdf

- Biophilia hypothesis – Wikipedia, accessed November 11, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biophilia_hypothesis

- The Six Principles of Biophilic Design — Vera Iconica Architecture, accessed November 11, 2025, https://veraiconica.com/the-six-principles-of-biophilic-design/

- Stephen R. Kellert, “Nature by Design The Practice of Biophilic Design” (Yale University), accessed November 11, 2025, https://environmentalhumanities.yale.edu/news/stephen-r-kellert-nature-design-practice-biophilic-design-yale-university

- The Six Principles of Biophilic Design – Neumann Monson Architects, accessed November 11, 2025, https://neumannmonson.com/blog/six-principles-biophilic-design

- Biophilic Design Barriers → Term – Lifestyle → Sustainability Directory, accessed November 11, 2025, https://lifestyle.sustainability-directory.com/term/biophilic-design-barriers/

- The six elements of biophilic design – Thermory, accessed November 11, 2025, https://thermory.com/blog-and-news/the-six-elements-of-biophilic-design/

- 4 Elements of Biophilic Design in Luxury Living Spaces – Ralston Architects, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.ralstonarchitects.com/biophilic-design/

- Stephen R. Kellert Biophilic Design Award – Living Future, accessed November 11, 2025, https://living-future.org/biophilic-design/award/

- 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design – Terrapin Bright Green, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/reports/14-patterns/

- 14 PATTERNS OF BIOPHILIC DESIGN – Terrapin Bright Green, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/14-Patterns-of-Biophilic-Design-Terrapin-2014p.pdf

- 14 P atterns of Biophilic Design – Global Wellness Institute, accessed November 11, 2025, https://globalwellnessinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/14patternsofbiophilicdesign.pdf

- 14+ Patterns of Biophilic Design – Terrapin Bright Green, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/report/14-patterns/

- Biophilia & WELL Building Standard – Terrapin Bright Green, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/blog/2015/07/biophilia-parallels-well/

- 14 PATTERNS OF BIOPHILIC DESIGN A REFERENCE GUIDE FOR ASSESSING THE PRESENCE – Terrapin Bright Green, accessed November 11, 2025, http://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/14-Patterns-Reference-Guide_v1.pdf

- The Economics of Biophilia – RICS, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.rics.org/news-insights/wbef/the-economics-of-biophilia

- Biophilic Design Makes Economic Sense Once You Look at These Data Points – TerraMai, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.terramai.com/blog/biophilic-design-makes-economic-sense/

- The Benefits of Biophilic Design in the Workplace | Planteria Group, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.planteriagroup.com/blog/the-benefits-of-biophilic-design-in-the-workplace/

- The Impact of Biophilic Design and Workplace Well-being – EHS Insight, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.ehsinsight.com/blog/the-impact-of-biophilic-design-and-workplace-well-being

- The Future of Design: Biophilia in Modern Architecture – Design Hotels™, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.designhotels.com/culture/design/the-future-of-design-biophilia/

- The Economics of Biophilia – Terrapin Bright Green, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/reports/the-economics-of-biophilia/

- Biophilic Design: Making the Workplace Livable – ISS World, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.issworld.com/en-us/insights/insights/blog/us/biophilic-design-livable-workplace-improve-productivity

- Biophilic Design in Hospitals: Natural Light on Patient Health, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.rockfon.co.uk/about-us/blog/2022/natural-light-in-healthcare/

- Biophilic Design as an Important Bridge for Sustainable Interaction between Humans and the Environment: Based on Practice in Chinese Healthcare Space, accessed November 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9271008/

- Biophilic Design Impact on Patient Recovery Rates → Scenario, accessed November 11, 2025, https://prism.sustainability-directory.com/scenario/biophilic-design-impact-on-patient-recovery-rates/

- A systematic review of the impact of therapeutical biophilic design on health and wellbeing of patients and care providers in healthcare services settings – Frontiers, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/built-environment/articles/10.3389/fbuil.2024.1467692/full

- Design guidelines for healing gardens in the general hospital – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed November 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10722422/

- Gardens in Healthcare Facilities: Uses, Therapeutic Benefits, and Design Recommendations, accessed November 11, 2025, http://www.healthdesign.org/sites/default/files/Gardens%20in%20HC%20Facility%20Visits.pdf

- Healing Therapeutic Garden at Kernan Hospital – Nature Sacred, accessed November 11, 2025, https://naturesacred.org/case_study/healing-therapeutic-garden-at-kernan-hospital/

- How to Use Biophilic Design to Earn LEED v5 Credits – Oakland …, accessed November 11, 2025, https://oaklandgreeninteriors.com/blog/how-to-use-biophilic-design-to-earn-leed-v5-credits/

- LEED v5 vs. LEED v4.1: Raising the Bar on Sustainable Design – Cove.Tool, accessed November 11, 2025, https://cove.inc/blog/leed-v5-v4.1-sustainable-design-architecture

- How to Achieve LEED v5 Credits with Biophilic Design – Benholm, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.benholm.com/blog/how-to-achieve-leed-v5-credits-with-biophilic-design/

- LEED v5 Preview #4: IEQ for Equitable Health and Wellness – LeedUser – BuildingGreen, accessed November 11, 2025, https://leeduser.buildinggreen.com/blog/leed-v5-preview-4-ieq-equitable-health-and-wellness

- IWBI: WELL – International WELL Building Institute, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.wellcertified.com/

- Using Plants To Become WELL Certified | Exubia, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.exubia.co.uk/biophilia-for-sustainability-and-well-being-certifications/

- Know Better, Do Better: Why Biophilia is the Future of Interior Design – Swatchbox, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.swatchbox.com/blog/Know-Better-Do-Better-Why-Biophilia-is-the-Future-of-Interior-Design

- Biophilic Design Certification: WELL Certification and Biofilico Wellness Interiors, accessed November 11, 2025, https://biofilico.com/news/biophilic-design-consultant-well-certification

- Healing Environments: Biophilic Design in Hospitals – Bison Blog, accessed November 11, 2025, https://blog.bisonip.com/healing-environments-biophilic-design-in-hospitals

- Biophilic Design for Healthcare – Garden on the Wall, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.gardenonthewall.com/blog/healing-spaces-applying-the-biophilic-interior-design-matrix-in-healthcare-design-in-healthcare

- Fostering the construction revolution – Cemex Ventures, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.cemexventures.com/biophilic-design-what-is/

- Interior Design Market Size, Share & Growth Report, 2030, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/interior-design-market-report

- Biophilic Integration Economics: Quantified Nature-Architecture ROI Models for Urban Development Competitive Advantage | by Ar. Prerana Kothari | Sep, 2025 | Medium, accessed November 11, 2025, https://medium.com/@Architects_Blog/biophilic-integration-economics-quantified-nature-architecture-roi-models-for-urban-development-20f414abc4dc

- The Economics of Biophilia: Retail – PRISM Sustainability in the Built Environment, accessed November 11, 2025, https://prismpub.com/the-economics-of-biophilia-retail/

- Opinion: Applications of and Barriers to the Use of Biomimicry towards a Sustainable Architectural, Engineering and Construction Industry Based on Interviews from Experts and Practitioners in the Field – PMC – NIH, accessed November 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11351985/

- What Are The Main Challenges And Solutions In Implementing …, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.benholm.com/blog/what-are-the-main-challenges-and-solutions-in-implementing-biophilic-design/

- What Is the Cost of Biophilic Design? → Question – Lifestyle → Sustainability Directory, accessed November 11, 2025, https://lifestyle.sustainability-directory.com/question/what-is-the-cost-of-biophilic-design/

- What Is the Lifecycle Cost Analysis of a Biophilic Building Compared to a Conventional One? → Learn – Lifestyle → Sustainability Directory, accessed November 11, 2025, https://lifestyle.sustainability-directory.com/learn/what-is-the-lifecycle-cost-analysis-of-a-biophilic-building-compared-to-a-conventional-one/

- Economic Impacts of Biophilic Urbanism: The Cost Savings, Cooling, Clean Air & Climate Benefits – Future of Cities, accessed November 11, 2025, https://focities.com/economic-impacts-of-biophilic-urbanism-the-cost-savings-cooling-clean-air-climate-benefits-of-integrating-botanical-designs-into-your-buildings/

- Healthy Dwelling: Design of Biophilic Interior Environments Fostering Self-Care Practices for People Living with Migraines, Chronic Pain, and Depression – PubMed Central, accessed November 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8871637/

- Ways Biophilic Design Promotes Human Health and Well-being – University of Central Arkansas, accessed November 11, 2025, https://uca.edu/art/2021/03/30/ways-biophilic-design-promotes-human-health-and-well-being/

- Biophilic Design Basics – Living Future, accessed November 11, 2025, https://living-future.org/biophilic-design/overview/

- Sustainable Designs: COOKFOX Architects – State of the Planet, accessed November 11, 2025, https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2014/04/25/sustainable-designs-cookfox-architects/

- Biophilic Architects: Architecture Studios for Biophilic Design — Biofilico Wellness Interiors, accessed November 11, 2025, https://biofilico.com/news/best-architecture-studios-biophilic-design

- The Fifth Façade: Designing Nature into the City – COOKFOX, accessed November 11, 2025, https://cookfox.com/news/the-fifth-facade-designing-nature-into-the-city-2/

- Three New Case Studies in Biophilic Design – Terrapin Bright Green, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/blog/2015/11/new-case-studies-biophilic-design/

- COOKFOX Green Roof, accessed November 11, 2025, https://cookfox.com/projects/cookfox-green-roof/

- Buro Happold and Cookfox Architects develop living facade for birds and insects – Dezeen, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.dezeen.com/2022/09/16/architectural-ceramic-assemblies-workshop-buro-happold-cookfox-architects-facade-design/

- Design for Health: The Next Decade of Positive Change – Mithun, accessed November 11, 2025, https://mithun.com/2021/04/19/design-for-health-the-next-decade-of-positive-change/

- Two New Case Studies in Biophilic Design – Terrapin Bright Green, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/blog/2016/04/two-new-case-studies-biophilic-design/

- Utilizing Mass Timber to Revolutionize the K-12 Market Sector – Mithun, accessed November 11, 2025, https://mithun.com/2024/09/24/utilizing-mass-timber-to-revolutionize-the-k-12-market-sector/

- People – Snøhetta, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.snohetta.com/people

- Biomimicry Co-Labs, accessed November 11, 2025, https://biomimicry.org/innovation/biomimicry-co-labs/

- How the Biggest US Companies are Integrating Biophilic Design – Plant Solutions, accessed November 11, 2025, https://plantsolutions.com/integrating-biophilic-design

- Looking Back On 25 Years Of The Healthcare Design Showcase – HCD Magazine, accessed November 11, 2025, https://healthcaredesignmagazine.com/trends/how-25-years-of-healthcare-design-showcase-changed-patient-care/160438/

- What is biophilic architecture? 15 real-world examples in the built environment, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.ube.ac.uk/whats-happening/articles/biophilia-examples-built-environment/

- Biophilia and Biophilic Design: 10 Tips and 4 Inspiring Examples – The Best Bees Company, accessed November 11, 2025, https://bestbees.com/biophilia-and-biophilic-design/

- Embracing Nature in Architecture: Top Nine Buildings Exemplifying …, accessed November 11, 2025, https://soltech.com/blogs/blog/embracing-nature-in-architecture-top-ten-buildings-exemplifying-biophilic-design

- Stanford Hospital: A Case Study – Perkins Eastman, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.perkinseastman.com/projects/new-stanford-hospital/

- Designing the new Stanford Hospital for patients and caregivers, accessed November 11, 2025, https://med.stanford.edu/news/insights/2019/06/designing-the-new-stanford-hospital-for-patients-and-caregivers.html